January 11, 2026 / by Fortify Labs / In information, connected vehicles, vehicles, privacy, Ford Ranger, Data Analysis

Behind the Dashboard: Part 2

Data Analysis – Ford Ranger

Welcome to the second post in our blog series:

Behind the Dashboard: Data Analysis – Ford Ranger

In Part 1, we outlined our strategy for this privacy demonstration, explained why we chose the Ford Ranger, introduced what a head unit is, and showed what the SYNC® 3 unit looks like—both intact and disassembled.

In Part 2, we take a closer look at the data extracted from the head unit we sourced from a wrecked vehicle.

To keep things clear and focused, here’s the series timeline:

Overview of strategy, vehicle selection, and introduction to SYNC® 3.

This post.

Where the Bluetooth Device data lives in the file system and the formats used.

Where the GPS and Driving data lives in the file system and the formats used.

How to run the infotainment system outside the vehicle.

Methods and tools used to access and read the memory chip.

What’s Inside the Infotainment System?

Most people think of an infotainment screen as a map, a radio, and a Bluetooth pairing menu. But once we imaged the SYNC® 3 unit from this Ford Ranger, we discovered something far more revealing:

The vehicle had kept an intimate diary of its owner’s life.

- Where they drove.

- Who they called.

- Every phone that connected.

- Stop and start locations, morning commute, late‑night drive, and weekend errands.

The system had captured enough detail to build a substantial picture of the previous owner and their family:

- Their full name — taken from their iPhone’s device name.

- Their home — the driveway they parked in most often.

- Their workplace — confirmed through GPS tracks and contact data.

- Their partner and two adult children — all identifiable through synced data.

- Call logs, contacts, and phone numbers from family members’ devices.

- Travel behaviours that painted a picture of daily life and routines.

- The precise moment and location of the accident that ended the Ranger’s use.

- And while no historic WiFi networks were present on this unit, our testing showed that any previously connected WiFi networks — including their passwords — would have been fully visible.

This wasn’t simply fragmented information — in the wrong hands, it would be enough to build a disturbingly accurate profile of the owner’s identity and behaviour. And it was all sitting, silently, inside the dashboard of a wrecked vehicle sold for parts.

The implications are hard to ignore:

A modern car doesn’t just take you places — it takes notes. And as our analysis shows, those notes can be incredibly personal.

Here is a visual summary of the information found:

How we did it

Determining the Likely Vehicle Owner

To identify the previous owner, we examined Bluetooth connection logs stored within the SYNC® 3 file system. Our working theory was that the device that connected to the head unit most frequently was likely the main driver’s phone.

Across the filesystem, we located several categories of Bluetooth-related logs. We focused on those containing detailed Hands‑Free Profile (HFP) connection events covering roughly three and a half months in 2025 — ending on the date of the vehicle’s accident. Within this period, three distinct Bluetooth devices connected to the Ranger’s head unit. After the accident, no further connections were recorded.

Connection counts for the three devices were:

- Device A: 280 connections

- Device B: 41 connections

- Device C: 33 connections

Based on this pattern, Device A was overwhelmingly the most frequently paired device, making it the most likely phone belonging to the primary user or owner.

Names of Owner and Family Members

Bluetooth pairing information also revealed the names of the people whose iPhones had connected to the SYNC® 3 system.

iPhones commonly include the owner’s real name as part of the device name — e.g., “David Smith’s iPhone” or “David’s iPhone.” This naming convention held true here: the main user’s full name appeared directly in the device metadata.

A total of five iPhones were identified in the logs. Two appeared to be older devices later replaced with new models. By comparing device names, models, and phone numbers, we were able to infer the likely first names of three additional individuals who used the Ranger:

- A female (likely the owner’s partner - which was further solidified with Open Source searches)

- A male (adult child 1)

- A second male (adult child 2)

We also identified iPhone upgrades for two of these individuals based on:

- The device name remaining consistent while the model changed.

- Identical phone numbers appearing across the old and new device entries.

In summary, the Bluetooth logs revealed:

- The likely owner’s full name (male).

- One female name.

- Two male names (likely adult children).

Phone Numbers, Mobile Network, Phonebooks & Call Logs

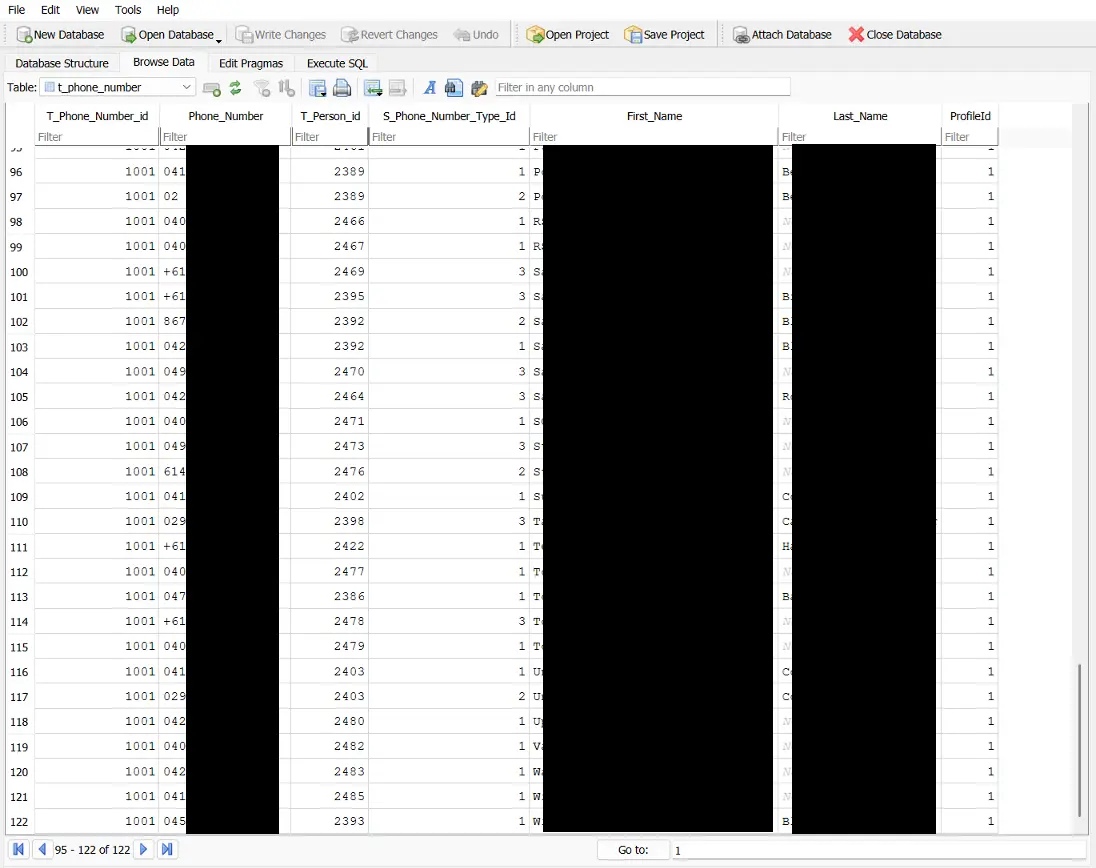

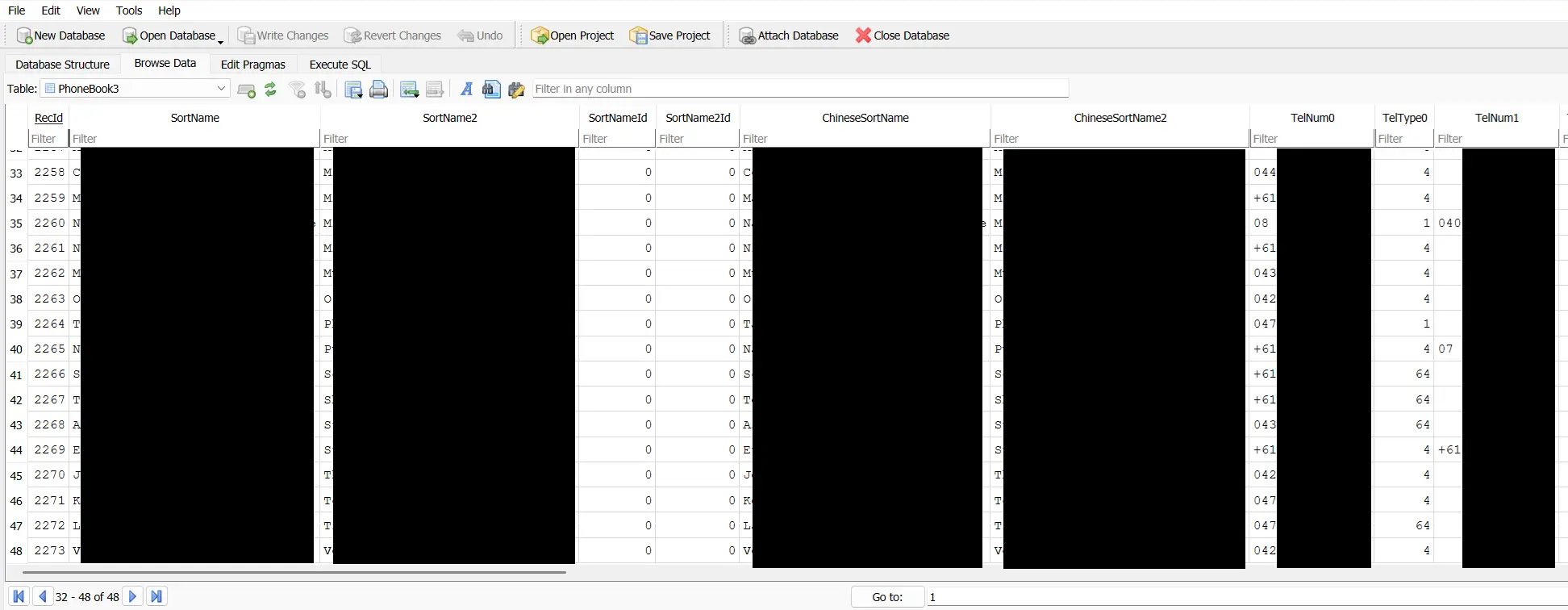

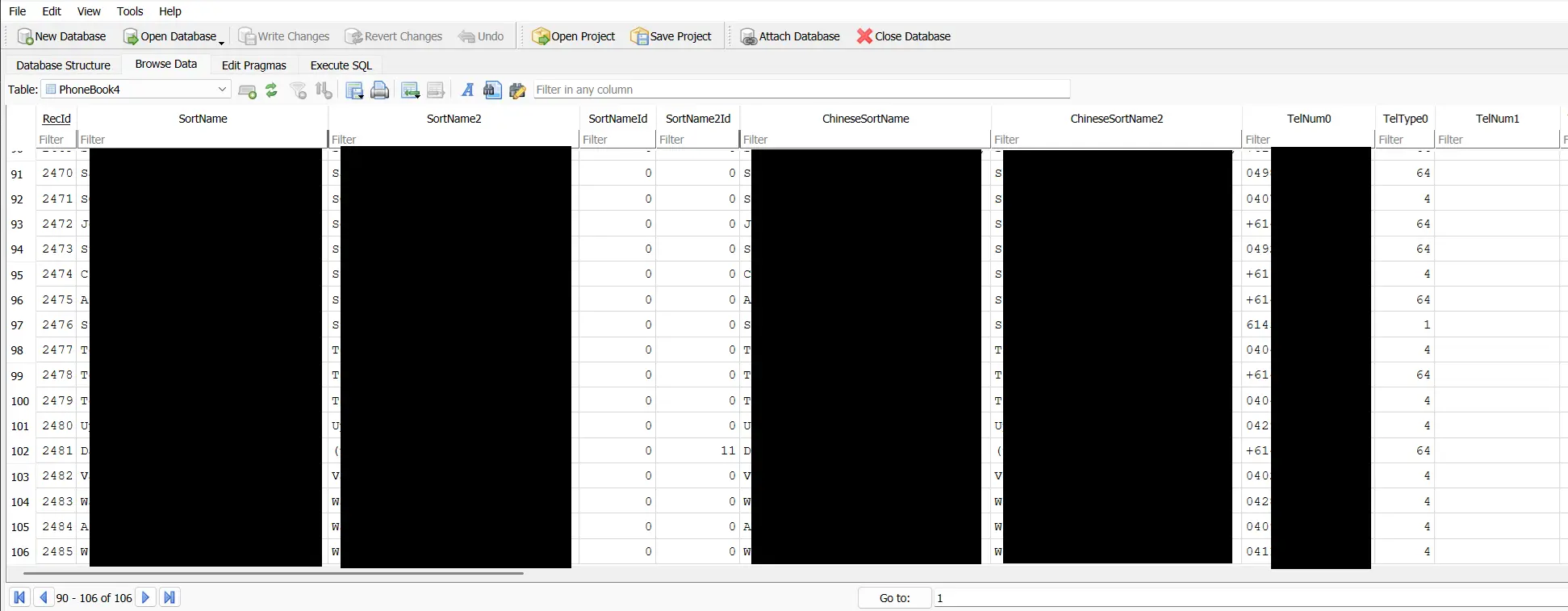

We then examined multiple databases related to phonebooks and call histories. These databases provided structured details about the devices that had connected to the Ranger’s SYNC® 3 unit.

Here is a consolidated view of the information recovered:

| Name | iPhone Model | Phone Number | Phonebook Entries | Call Logs Records | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First and Last (owner) | iPhone 11 Pro (May 2025 update) | Yes | None Found | None Found | Likely the main user/owner. No call logs or contacts saved. |

| First Name (Adult Child 1) | iPhone 11 Pro (Nov 2023 update) | Yes | N/A | N/A | Older device, likely replaced. |

| First Name (Adult Child 1) | iPhone 15 Pro (May 2025 update) | Yes | 57 Entries | 63 Call Logs | Newer device, with data synced. |

| First Name (Adult Child 2) | iPhone 12 (Sep 2023 update) | No | N/A | N/A | Older device, likely replaced. |

| First Name (Adult Child 2) | iPhone 15 Pro (Apr 2025 update) | Yes | 122 Entries | 57 Call Logs | Newer device, with full data synced. |

Only the two adult children’s updated devices contained synced phonebooks or call logs. This suggests that only those individuals granted contact and call‑history access during the Bluetooth pairing process.

Cross-referencing entries revealed contacts labelled “Mum” and “Dad.” The phone number for “Dad” matched the owner’s device, providing a secondary confirmation of the family relationship.

Call Logs and Phonebook entries

The SYNC® 3 filesystem contained multiple databases corresponding to phonebooks and call histories. Although several phones had connected over time, only the two adult children’s devices left behind actual data. This is expected behaviour: SYNC® 3 would only store contact and call history information when the user explicitly allows access during Bluetooth pairing.

Interestingly, the two devices each appeared in more than one database, and each database contained a different number of entries. While we did not conduct deeper analysis to determine why, the most likely explanation is that different subsystems within SYNC® 3 maintain their own contact databases for different functions (e.g., voice recognition, on‑screen dial pad, call history interface).

Each of these databases is updated independently based on when those functions are used.

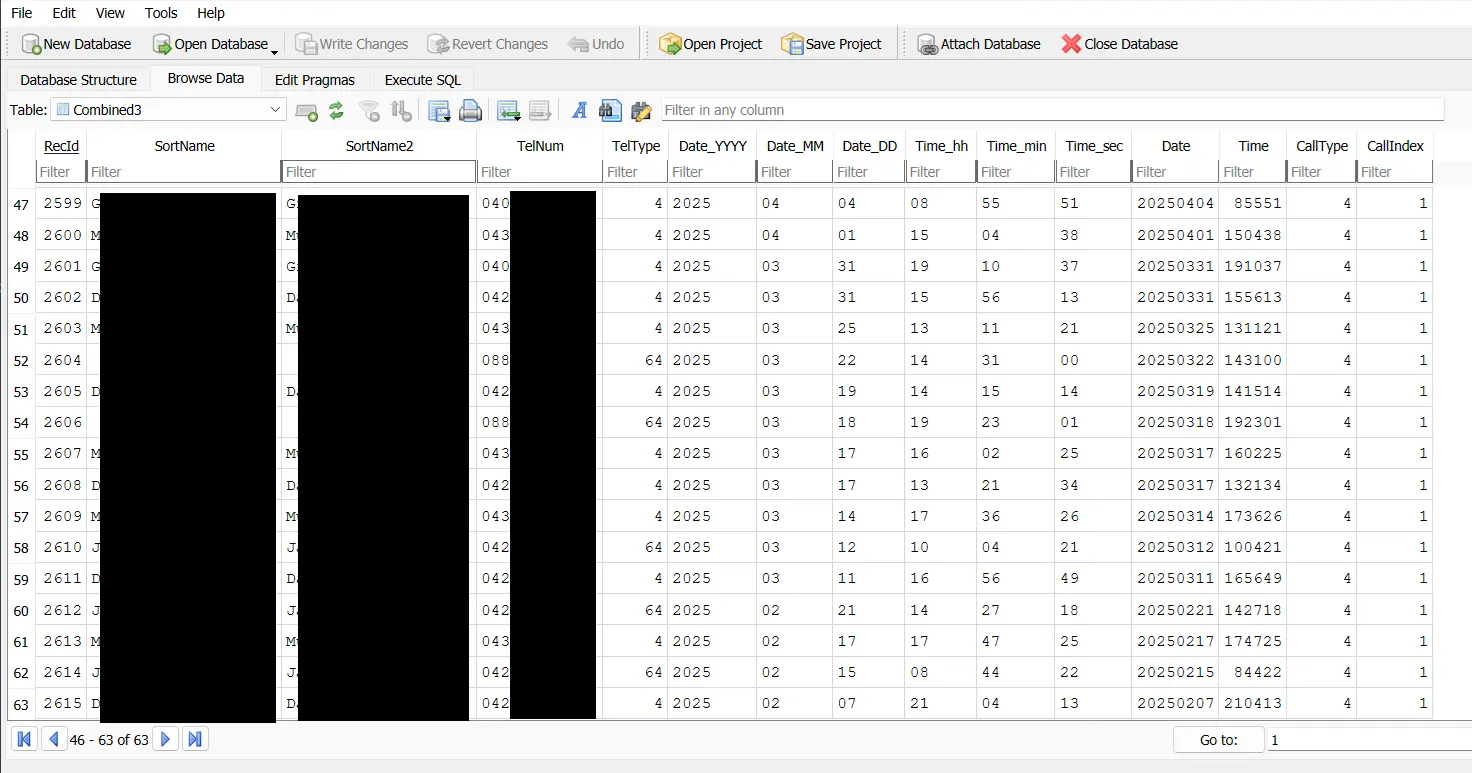

Call Log Records

Below are screenshots showing call log records for the devices associated with Child 1 and Child 2.

- Child 1 - 63 Call Records Found

- Child 2 - 57 Call Records Found

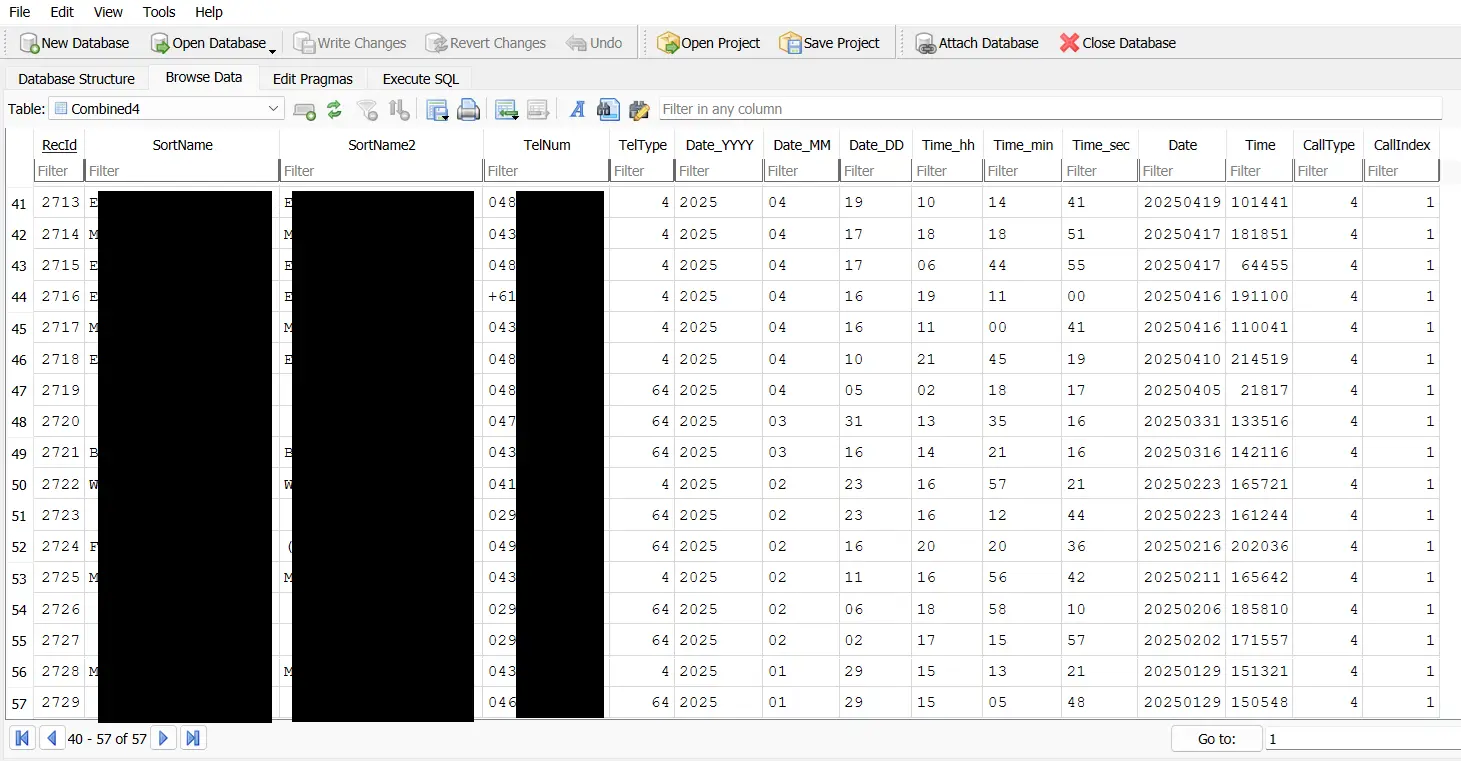

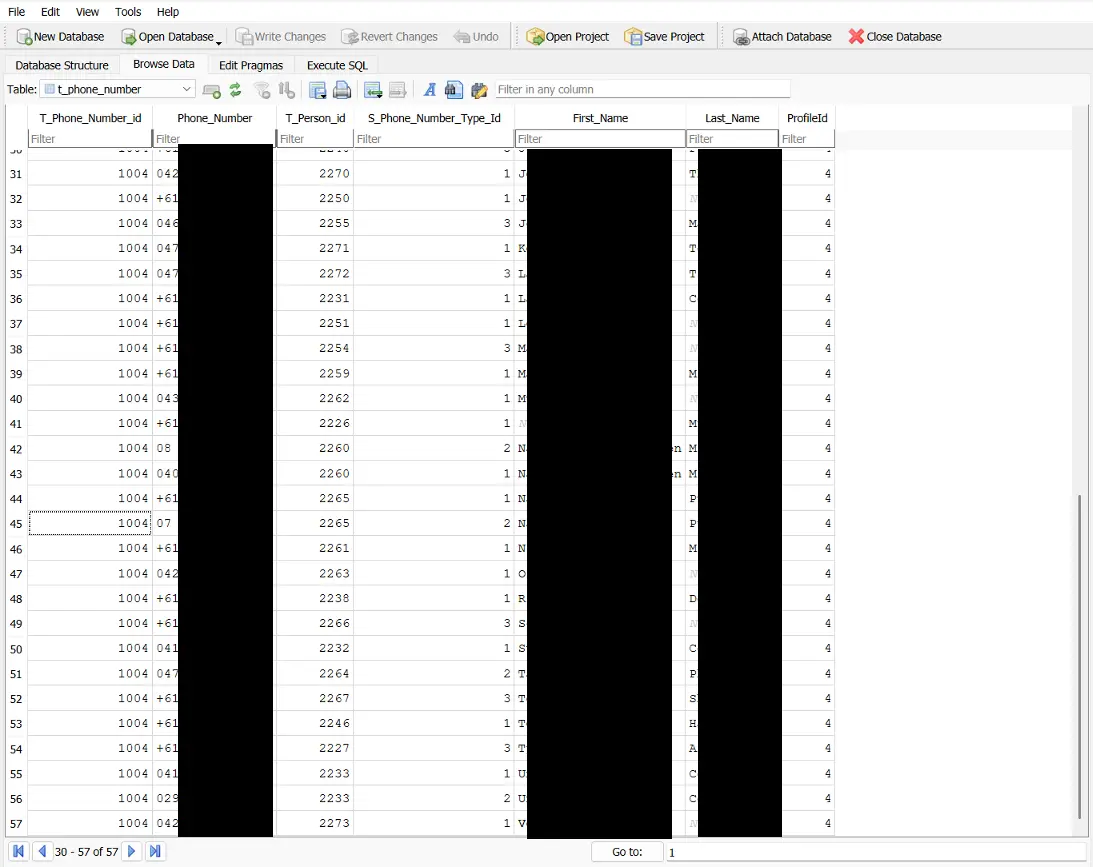

Phonebook Entries

Below are screenshots showing the phonebook entries associated with the devices linked to Child 1 and Child 2.

- Child 1 - 57 Phonebook Entries Found

- Child 2 - 122 Phonebook Entries Found

Below are screenshots from phonebook entries belonging to the devices associated to Child 1 and Child 2 found in a different folder (and therefore used by a different system function).

- Child 1 - 48 Phonebook Entries

- Child 2 - 106 Phonebook Entries

Confirmation of Family Connections - via Open Facebook Profile

During our analysis, we performed a simple Google search using the name extracted from the owner’s iPhone device entry. This led us to a publicly accessible Facebook profile that matched the same name. Because portions of the profile were visible without logging in, we were able to cross‑reference information from the SYNC® 3 data with publicly posted details.

Although this post focuses primarily on what a vehicle can reveal about its owner, this step serves as an important reminder: public social‑media profiles can unintentionally expose additional personal information when combined with data from other sources. From a brief review of the open Facebook content, we were able to validate several of our earlier inferences:

- Workplace: The GPS‑derived work location aligned with the business listed on the owner’s profile.

- Partner: The female name found in the Bluetooth logs matched the partner’s name on Facebook.

- Children: The two male names identified from connected devices matched the names of the owner’s adult children visible on the profile.

- Birthday Indicator: A birthday post from the partner provided a likely birth date for the owner.

This corroboration highlights how easily vehicle‑stored data can be paired with publicly available information to form a much more complete picture of a person’s identity and family relationships.

With the family relationships and identity indicators now corroborated, the next step was to analyse the vehicle’s location data. That information turned out to quite revealing.

GPS Information

Multiple files and directories within the SYNC® 3 filesystem contained GPS data related to the vehicle’s movements. The most detailed information was located in a set of log files inside a directory named fordlogs.

These logs included high‑resolution GPS track data covering trips taken between 27 July 2025 and 10 November 2025. Across this period, we identified:

- 66 individual trip tracks.

- Representing 44,709 GPS points.

- With location data recorded every second while the vehicle was in motion.

Note: For simplicity, individual “tracks” were defined by identifying gaps of at least two minutes between successive GPS points.

Using these logs, we were able to determine the date, time, and precise location of the accident that occurred in early August 2025.

After the accident, additional GPS data continued to appear, but with minimal movement — consistent with the vehicle being powered on at repair facilities, tow yards, and eventually a wrecking yard.

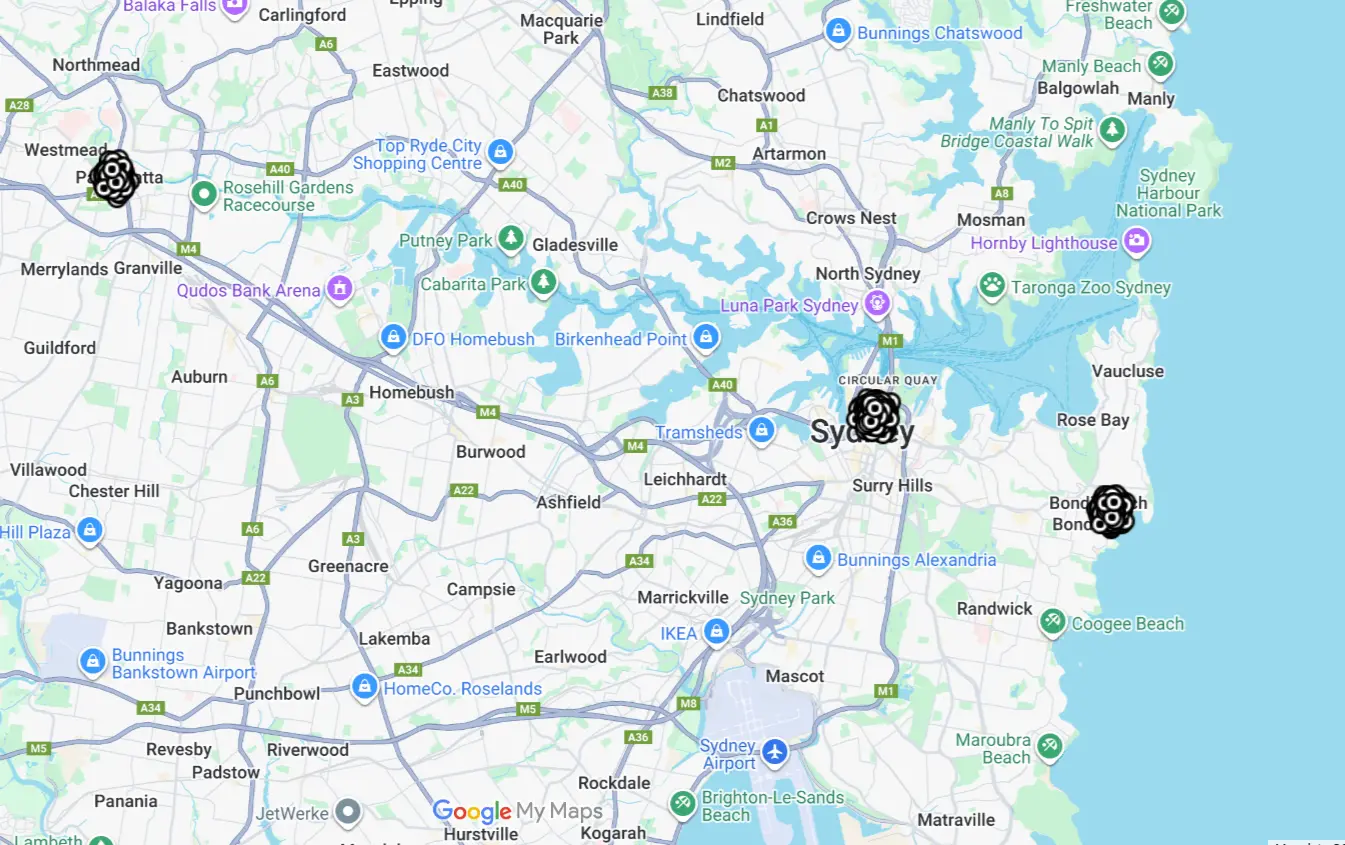

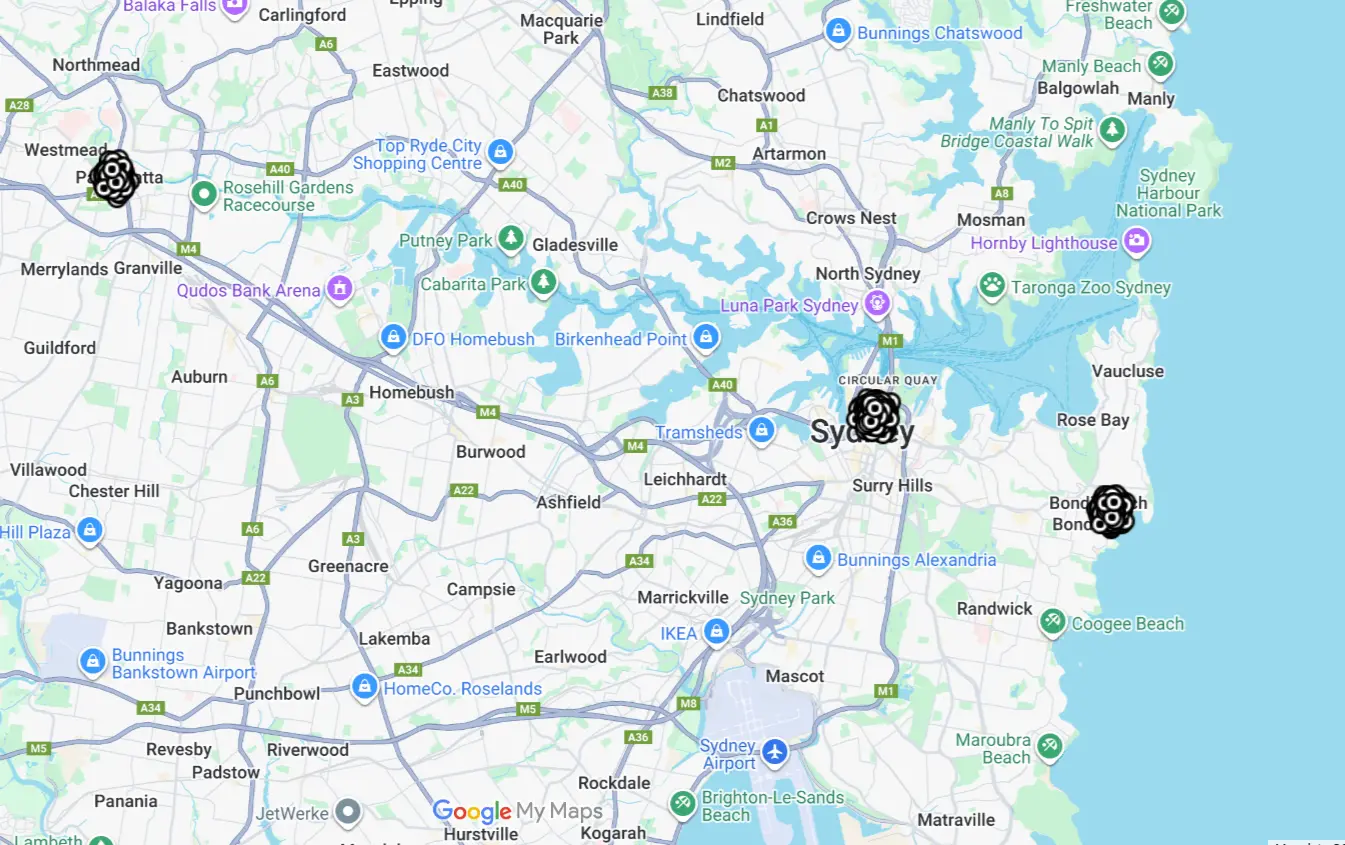

The screenshot below demonstrates how a subset of the exported GPS points can be visualised in Google Maps to reconstruct the vehicle’s path.

Note: All geographic specifics have been deliberately obfuscated. Start and end points have been removed to avoid revealing any information about the previous owners or their locations.

From this information, someone could:

- Estimate general speed patterns, providing insights into driving behaviour.

- Identify highly specific stop locations, revealing potential home, work, school, and frequently visited points such as shops or regular errand stops.

Home & Work Locations

To identify potential home and work locations, we analysed a different set of GPS records found within the NAV directory. These logs appeared to record the vehicle’s location every time the SYNC® 3 system booted. For each boot event, the system also attempted to associate the current coordinates with nearby points of interest—presumably to display fuel stations, parking, or other local information when the vehicle started.

Across the full dataset, the SYNC® 3 system:

- Booted 8,461 times

- Across a date range from 2022‑02‑03 to 2025‑11‑10

These logs effectively provided a multi‑year record of when and where the vehicle was started, from its normal daily use right through to its movements after the accident.

For this analysis, we limited our focus to boot events recorded in 2025. From these points, we clustered nearby coordinates (using ~100 m precision) and calculated the centre of each cluster. The three most frequent start‑location clusters were then plotted on Google Maps to understand their significance.

Overview

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| Total GPS Points | 1,870 |

| Unique Locations (clustered) | 156 |

| Date Range | 2025-01-02 to 2025-11-10 |

| Clustering Precision | ~100 meters |

Top 3 Most Common Locations

| Location | Total Points | Percentage | First Visit | Last Visit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location #1 | 559 | 29.9% | 2025-01-02 08:42:31 | 2025-08-01 14:31:06 |

| Location #2 | 433 | 23.2% | 2025-01-02 14:57:53 | 2025-08-01 16:05:12 |

| Location #3 | 160 | 8.6% | 2025-01-02 11:09:18 | 2025-08-01 13:58:14 |

Combined Statistics

| Category | Points | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Top 3 Locations Combined | 1,152 | 61.6% |

| Other Locations | 718 | 38.4% |

Interpretation of Frequent Start Locations

When plotted on Google Maps, the pattern became clear:

-

Location #1: This cluster corresponded to a point immediately outside a business. This was confirmed through publicly visible Facebook posts that this business was the correct workplace of the main user. The business name also appeared in one of the synced phonebooks.

-

Location #2: This cluster centred directly on the driveway of a residential property. Given that it accounted for over 23% of all start events in 2025, it is very likely the owner’s home.

Another Open Source search including the newly obtained address as well as the surname uncovered a publicly listed record from a local council in 2017 referring to a shed and carport development application. This document included the land Lot number, street name, and last name of our family — supporting this conclusion.

- Location #3: While visited less frequently, this point appeared consistently enough to indicate a regular destination — potentially a secondary workplace, school, family member or friend’s residence, or recurring errand location.

Below is an illustrative example showing how the three location clusters appear when visualised. These coordinates are randomised to be located across Sydney to ensure no real locations are revealed. The point density (i.e number of points) reflects the behaviour of the actual data.

Other Vehicle Data

In addition to personal information and location logs, the SYNC® 3 system also stored a range of other data points related to the vehicle’s behaviour and surrounding environment. These additional logs provide further insight into how the vehicle was used and what information it retained during day‑to‑day operation.

WiFi Access Points

As part of our analysis, we discovered that the Ranger’s SYNC® 3 system recorded details of WiFi access points it encountered while powered on. Modern vehicles may use nearby WiFi networks for a variety of reasons, including navigation assistance, location refinement, or connectivity management (such as automatically connecting to previously saved networks).

From the collected logs, we were able to identify:

- WiFi networks seen during travel.

- Previously connected access points (in our case, none were found).

- The potential presence of WiFi routers near frequently visited locations.

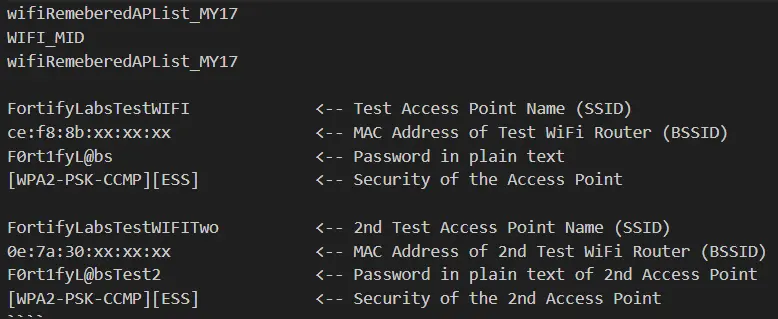

To better understand how SYNC® 3 stores this information, we conducted additional testing in the lab:

- We booted the extracted head unit.

- Connected it to two separate test WiFi networks.

- Created a new memory image.

- Searched the filesystem for corresponding WiFi entries.

In the updated image, we found a configuration file containing the names of each connected WiFi network and their passwords stored in plain text.

Below is a cleaned example of the recovered test data (with MAC addresses partially redacted):

This confirms that if the original owner had connected the Ranger to a home, work, or mobile hotspot, the network name and password would have been available within the infotainment system’s memory.

Emergency Alerts

During our examination of the SYNC® 3 filesystem, we also identified log entries indicating that the vehicle had detected an Emergency Event, consistent with a crash. These entries were timestamped and included references that aligned directly with the accident date earlier identified in the GPS data.

By correlating the emergency‑event logs with the high‑resolution GPS tracks, we were able to confirm:

- The exact date and time of the collision.

- The precise GPS location where the crash occurred.

- The vehicle’s behaviour immediately after the impact, including minimal movement while powered on.

The sequence of events presented a clear pattern:

- The crash was recorded on an afternoon in August 2025.

- Shortly after the event, the GPS logs showed the vehicle powered on but moving only a few metres—consistent with post‑accident conditions.

- Several hours later, the vehicle started again a few kilometres away. Mapping this location revealed it to be a tow or repair facility.

- Over the following months, sporadic GPS points showed the vehicle at various service and storage locations.

- Eventually, the logs placed the vehicle thousands of kilometres away, matching the wrecking yard from which the SYNC® 3 unit was purchased.

These logs highlight that SYNC® 3 not only records travel behaviour, but also retains detailed information about significant vehicle incidents—all of which remain stored long after the event itself.

Specific Details of Last Use

Another set of logs—found within a directory named ccl — provided a detailed record of the Ranger’s final days of operation.

These logs appear to capture session‑level information each time the vehicle was powered on, including ignition state changes, gear‑shift activity, door events, navigation activity, and short‑duration movement.

From this data, we identified what appears to be the final day the vehicle was powered on and moved (prior to the head unit being removed), which occurred in November 2025. The GPS history confirms that by this point the vehicle was located at the wrecking yard, several thousand kilometres from its usual operating region.

Based on the ccl logs, the Ranger was used in three distinct sessions on that day:

- Session 1:

- The vehicle was powered on (ignition in accessory mode), but the engine was not started and the vehicle did not move.

- Session 2:

- The ignition was switched to RUN and the engine started.

- The driver’s door opened and closed multiple times, and the transmission was shifted repeatedly between Park, Reverse, and Drive.

- Although the vehicle moved only a short distance—estimated at 10–15 meters—the log captured gear transitions, timing, and low‑speed movement with notable precision.

- Session 3:

- The vehicle was powered on again, with additional brief engine starts and door events.

- Movement was minimal, consistent with positioning or manoeuvring the vehicle within the wrecking yard.

The logs also recorded the vehicle’s odometer reading, showing a final mileage of 58,541 km.

Additionally, these files referenced a URL:

https://www.cloud-sync.ford.com/analytics/v1/client-data.

This suggests that at least some of the information recorded in these logs may be intended for transmission back to Ford’s analytics systems when connectivity is available.

Overall, the ccl logs provide a granular snapshot of the Ranger’s final interactions—down to ignition sequences, gear selections, and brief movements—long after the vehicle’s accident and primary service life had ended.

Timeline Analysis - Boot Sessions

Below is an example of three consecutive boot cycles from the last day of use, summarised for clarity.

Boot Cycle No. 9049

| Property | Value |

|---|---|

| Time Range | 04:04:34 - 04:04:13 |

| Duration | 20 seconds |

| Ignition | OFF → OFF |

| Gear Changes | P (1 change) |

| Status | Vehicle stationary |

| Navigation | Active 54 sec |

Boot Cycle No. 9050

| Property | Value |

|---|---|

| Time Range | 05:04:29 - 05:07:08 |

| Duration | 2 min 39 sec |

| Ignition | OFF → RUN → OFF |

| Door Activity | ajar → closed → ajar → closed |

| Gear Changes | 13 total |

| Max Speed | 0.56 km/h |

| Navigation | Active 2 min 13 sec |

Boot Cycle No. 9051

| Property | Value |

|---|---|

| Time Range | 05:07:51 - 05:09:11 |

| Duration | 1 min 20 sec |

| Ignition | OFF → RUN → OFF → START → RUN → OFF |

| Door Activity | ajar → closed (3 times) |

| Gear Changes | 8 total |

| Max Speed | 0.84 km/h |

| Navigation | Active 56 sec |

Note: Interpretation of these fields involved informed assumptions based on log structure and behaviour. Additional controlled testing would be required to confirm the exact meaning of every event with full certainty.

Conclusion

This analysis makes one thing clear: your vehicle remembers far more about you than you might expect. Even a discarded head unit held a detailed record of its owner’s movements, habits, and relationships.

And while this particular unit came from a wrecked vehicle, the same risks apply when selling a used car or even renting a vehicle — any infotainment system that has paired with your devices or recorded your travel history may still contain deeply personal information unless it is properly wiped.

As we move into the next part of the series, we’ll show exactly where this data lives inside SYNC® 3.

Next Up

In Part 3, we’ll take a technical deep dive into where this data resides within the SYNC® 3 file system and the formats used to store it.

Stay tuned as we continue uncovering what’s really happening behind the dashboard.

Disclaimer

This analysis reflects our professional experience and represents our best interpretation of the log entries available at the time of extraction. It should not be considered definitive evidence for legal proceedings without independent verification of the data and validation of any assumptions made during the analysis.

We have made every effort to obfuscate or remove any details that could identify the previous owner(s) or their devices.